I first met Bob Reinert in 1954 at New England Music Camp in Maine. He had just completed his first year teaching in the Crane School of Music at Potsdam State Teachers College (now SUNY at Potsdam) and was in his first summer in residence at the camp, a relationship that was to last for more than three decades; I was an aspiring teen-age double bass student who was only vaguely aware of the bassoon’s existence. All that was about to change. I spent a good deal of that summer perched on my bass stool in the student orchestra, transfixed by that incredible sound coming from the bassoon section. The next summer, I came back with a bassoon and started studying with him. The double bass quickly became a secondary interest for me; and my life, for better and for worse, was never quite the same thereafter.

After I had taken three bassoon lessons over the first few weeks, Dr. Paul Wiggin, the camp’s autocratic director and also its resident band director, came up to me after dinner one night and started out with “Now, David…” I knew him well enough to know he was about to make me an offer I didn’t dare to refuse. He said, “Now, David, Mr. Reinert says you are ready to begin playing bassoon in the band next week.” I suspected that Mr. Reinert had said no such thing, but had probably gotten a similar ultimatum from his boss. I was about to protest, but I was also mindful that nobody ever said no to Paul Wiggin. He ran a very tight ship up there in Central Maine. I realized only later that there was a method in his madness. He wanted me to be up to speed on bassoon by September so I could play creditably in his high school band.

So I showed up the following Tuesday to band rehearsal at 8:10 A.M. on a very chilly Maine summer morning in July. Reinert pointed me to an empty chair on his right side, his other bassoon students being arraigned on his left, obviously with the intention of keeping a close eye on me. The first piece up was a concert march in the key of Eb -- I can’t remember which one any longer. I was doing OK for the first five minutes – and then came the Trio, which was in Ab major and required a Db. I didn’t know how to play a Db – I hadn’t gotten that far in the Weissenborn method yet! I leaned over to my teacher and said, “Psst! How do I finger Db?” He said, “you just finger C and with your left thumb you hold down this key – and this key – and this key.” I thought he was kidding me. I turned and looked at him and said, “That’s impossible!” But of course it wasn’t impossible, just difficult for a newbie like myself to master on the fly. I learned an important lesson from my teacher that day about bassoon playing: the difficult we are expected to do immediately; the impossible takes just a little longer. By the end of the rehearsal, I had more or less gotten the hang of it.

Later that same summer, I underwent my baptism by fire in the camp’s orchestra. The piece in question was the Prelude to the 3rd Act of Lohengrin by Wagner, which requires three bassoons. Unfortunately there were only two bassoonists in the orchestra, Reinert and one of his other more advanced students. He recruited me to play the third bassoon part. At the last rehearsal, he told me I needed a better instrument than my high school’s junker bassoon that I was playing in the band. So he loaned me a new Heckel bassoon which he had just recently obtained from Hugh Cooper. He preferred his ancient 5900 series Heckel bassoon, as indeed he did for the rest of his life. So I played the dress rehearsal and concert on a brand-new, wholly unfamiliar instrument worth a small fortune on loan from my teacher. His generosity to me, then and continually over the next half century, was indeed humbling.

I soon learned that Bob Reinert’s speaking voice, his singing voice, and his playing voice were all one in the same. He could pick up a student-quality saxophone or clarinet and get that same remarkable sound that he produced on his beloved old Heckel bassoon: dark, warm, rich, resonant, and above all seemingly effortless. For the next twenty years, I avidly pursued bassoon playing as a career, in the process studying with several other noted symphony musicians while in college and graduate school, but Reinert always remained my model and ideal as a player and as a musician.

More than perhaps anyone else I ever met, Reinert taught by example rather than by fiat. He generously shared his time and knowledge with each of his many students. His approach to music-making was, for want of a better term, an holistic one, a way of thinking and feeling about music as well as performing. He sang, he played, and one learned more by a process of osmosis than by structure. Virtually every student who came into contact with him wanted desperately to emulate his remarkable sound and style of playing. Yet I think it safe to say that none of those who attempted to reproduce his unique sound came even remotely close, even after a lifetime of tinkering with reeds, bocals, instruments, and playing techniques.

After completing my doctoral studies in the early 1970s, I decided to devote myself to working with and performing on historical wind instruments, all of which were even more recalcitrant and unstable than the modern bassoon. I gradually learned that Reinert’s approach to singing and playing could be applied equally profitably to a wide variety of other instruments as well. I came to understand that his techniques were in fact universal ones and quite likely authentically historical ones as well, although he himself had little interest in historical instruments and performance practices. In more recent years, I was finally able to explain to him what he did from an acoustical standpoint while playing and singing, although how he did it still continues to elude me to this day.

In recent decades, Bob and his wife Peg would visit Julie and me in Brookline and later in Plymouth each summer, until his gradually declining health made these annual trips north from his retirement home in Florida no longer possible after 2003. Our decades-long dialog would continue before he even got out of the car and was still going on as he drove away days later. We would talk not just about bassoons, bassoonists, and bassoon playing, but about the musical world in general, as well as our mutual passions in audio equipment, automobiles, food and wine, and every other conceivable topic under the sun.

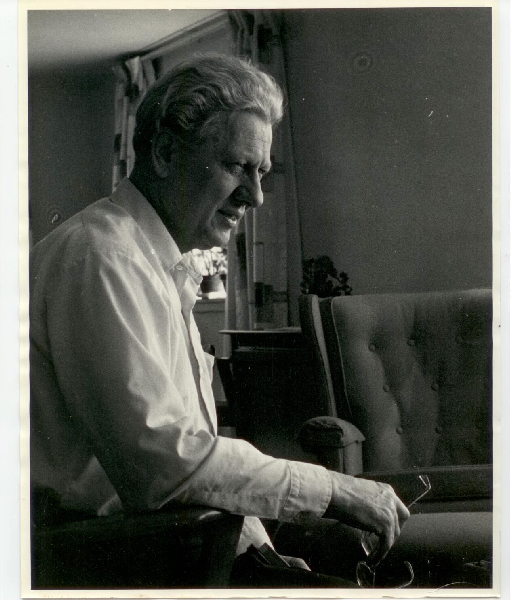

Bob Reinert was my teacher, mentor, friend, father figure, and the major influence on my musical career. Perhaps more than anything else, he was an abiding presence in my life for over half a century. Those of us who studied with him and loved him would dearly like to believe that he founded a school of bassoon playing and created a dynasty of successors to carry on his philosophy and techniques. Yet all of his students turned out to be very different kinds of players and musicians. The elusive ideal that he embodied could be pursued but unfortunately never attained. The real truth is that Charles Robert Reinert was a singular individual and a unique musical talent, one that could not be replicated. And now he belongs to the ages. All the rest is silence.

David H. Green, director

Antique Sound Workshop, Ltd.A memorial celebration of the life of Charles Robert Reinert was held in Helen Hosmer Hall at the Crane School of Music, SUNY at Potsdam, on Friday, September 21st, 2007 at 1:00 P.M. A reception for his family, friends, and students followed.